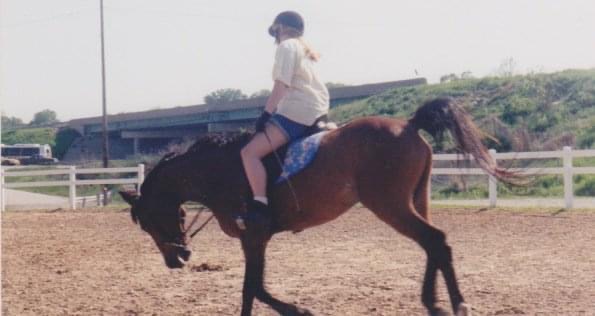

Back in the 90s, I learned to ride with a dressage foundation. What that gave me was a great perspective on feeling the horse, responding to them, and being effective with my aids. As time has passed over the last 30 years or so, the learnings and the sport have evolved. Because I didn’t really take dedicated lessons for any long stretch of time after about 1997, and because the internet wasn’t the vast resource it is today, I stopped evolving in my knowledge as well. I did pick up new things, good and bad, over the course of riding a variety of horses and I was lucky enough to always at least be around people for whom the welfare of their horses was paramount. However, it wasn’t until recently that I really started learning to connect the dots when it came to animal welfare, equine biomechanics and behavior, and modern riding and training.

Before I got my own horse, I began attending clinics online and in the real world, many of those starring Deanna Pries of Shadetree Stables, who does an excellent job of bringing together the physical, mental, emotional, and tactical elements of equestrian training. Through her and her biomechanics approach to dressage, I started to understand the whys behind terms I’d always heard, like engagement, self carriage, etc. To be honest, I didn’t even REALLY know what self carriage was. I started to figure out the things I was taught in those early days that were helpful and things that were…not so much.

For example, I was taught early on to encourage the horse to “stretch” by see-sawing the reins and giving length straight down to the buckle as the horse kind of just dove down toward the ground with their head. It was meant to help the horse lengthen through the topline and become more supple. In theory, the suppled up horse would be more receptive to being “on the bit,” meaning the rider would be able to take up contact on the reins and have the horse be able to lean into the contact. However, what I later learned was that stretching all the way down actually has diminishing returns from a biomechanics perspective.

Self carriage stems from what is known as the thoracic sling, a set of strong muscles in the chest and rib cage to help connect the horse’s front limbs to their trunk, in place of a clavicle. If a horse does not have a strong thoracic sling, they can lack balance and stability. Without strengthening the thoracic sling, which is often referred to as the horse’s “core” (they don’t have six packs), you won’t have proper engagement from back to front, which is the entire basis of dressage. When a horse dives their head straight down to push peanuts on the ground, the core collapses, which then creates a hollowness in the back and causes the hind legs, which are supposed to be engaged and supporting movement from under the body, to camp out further back behind the horse. Overall, this is a pretty bad position from which to carry a rider as it causes the horse to balance and support their own weight and the rider’s weight basically on the front legs and shoulders.

So, all that time I spent thinking I was making my horse so supple, I was actually weakening him. The proper stretching position looks more like a dolphin, where there’s a bit of a bascule to the neck and the nose is down and searching forward, usually stopping around the knee area or just below the shoulder. But, to achieve that, the horse needs to have better balance and an engaged thoracic sling.

Another thing I learned is that the position of the head should be dynamic and not fixed. So, even if the horse is allowed to stretch, they won’t keep their head in that position constantly. The head and neck help the horse balance, so, until a horse is perfectly balanced (which is a mythical situation), they will often come up and down out of that position.

Yet another thing I “unlearned” was see-sawing the bit in the mouth. This can actually cause a horse to stiffen or lock the jaw and does not encourage softness. What is the solution? Again, it’s balance. You can’t shortcut your way to your desired headset, in essence. You’re better off working patterns and circles and moving the horse off your leg with an elastic and mildly playful feel of the bit, giving the horse the opportunity to find balance, relax, and start to drop their head. This, unfortunately, takes a LOT of time, especially with a tense and unbalanced horse like mine, who sadly has a rider who is unlearning a lot of old, bad habits (like riding with straight arms from years of working “on the buckle”), and finding a better dressage seat.

But “once you know better, you do better,” as Deanna says. And that’s what I intend to work on.